A Brief History of Kinetic Art

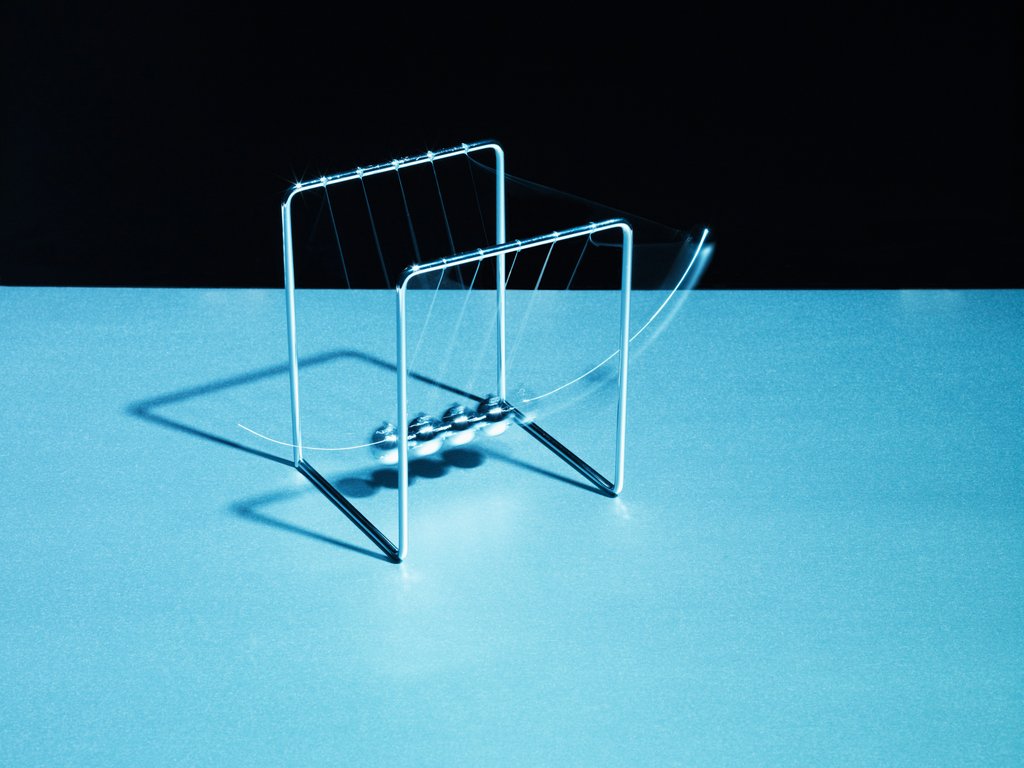

When we were children, some of us can probably remember shuffling past a plain grey office desk or walking down a hallway and stopping to stare at a decorative table. Our eyes probably wandered, as they had hundreds of times before, to whatever was sitting on these desks and tables. We would have caught a glimpse of a set of swaying metal balls strung up to a stand. This experience would have been our first encounter with the essential office gadget: Newton’s Cradle. If you aren’t familiar with Sir Isaac Newton’s cradle, it’s essentially a desk toy which demonstrates Newton’s theorems on gravity. These objects today are still present and beloved across the world. They are the predecessors of the artworks which we call now as Kinetic Art.

YHE BIRTH OF THE EXECUTIVE TOY

In the late 60’s Simon Prebble, an English actor coined the name of the famous metal swing set, however “Mr. Prebble’s greatest challenge was convincing serious business people to buy something without an apparent purpose” (Antonick). Ultimately, despite the challenge, the actor managed to catapult the Newtonian sculpture onto the shelves of department stores like Harrods. It was sold as an “executive toy” to the white-collared masses. It was undeniable that this object had an inherent attraction. Furthermore, it represented a fledgling movement of sculptures and art installations ranging from the minuscule to the massive – which had the intention to impress and educate.

Pin Toys, another example of the first kinetic creations, is a screen of pins that would take the shape of anything which applies pressure to it. Ward Fleming, the inventor of these pin screens, had a similar aim to Prebble, he wanted a way for people to connect to animation and the science of three-dimensionality. Another “executive toy” of note predates both the cradle and the pin screen. Miles Sullivan’s 1945 Drinking Bird used thermodynamics and water evaporation to create a wooden-glass bird that could consistently tip up and down while seeming to drink from a glass of water.

Kinetic Toys in Movies

All these creations had a common goal: using inherent principles of science, nature, and mathematics in playful installations and trinkets. Funnily enough, these playthings became so popular that they appeared In Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film “Brazil”. When the protagonist is given “something for an executive”, the film attempted to make a mockery of the bobbling balls and dipping birds. The very fact that they were the center of attention in a scene within a major Hollywood film shows us why these kinetic toys became so iconic. In fact, Newton’s Cradle alone appeared in over 37 cinema productions, ranging from “The Matrix” to “Concussion”.

As funny and trivial as we may find these ornaments, they stand for something far larger. The kinetic art revolution began as a response to modern advances in science and technology, as the world was vastly shifting its focus from classics to scientific discovery, sculpture and sculptors had absolutely no intention of being left behind, and so they innovated and broke the restraints of the standards set by their predecessors. Moving works of art began to storm public squares and the monochrome hallways of the workplace. Many artists simply wanted to comment on the connection between man and machine, following the essential rites of Dadaism and industrial art; however, a number of artists such as Naum Gabo, Marcel Duchamp and Alexander Calder continued to create works that were inspired by science and designed in the spirit of teaching and inspiring. Pieces such as “Standing Wave” and Calder’s mobiles used natural principles of air-flow and gravity to allow the sculptures to speak for themselves.

THE KINETIC ART REVOLUTION

As funny and trivial as we may find these ornaments, they stand for something far larger. The world was vastly shifting its focus from classics to scientific discovery. The kinetic art revolution began as a response to modern advances in science and technology. Sculpture and sculptors innovated and broke the restraints of the standards set by their predecessors. Moving works of art began to storm public squares and the monochrome hallways of the workplace.

Many artists simply wanted to comment on the connection between man and machine, following the essential rites of Dadaism and industrial art. However, a number of artists such as Naum Gabo, Marcel Duchamp, and Alexander Calder continued to turn to science as inspiration; they designed in the spirit of teaching and inspiring. Pieces like “Standing Wave” and Calder’s mobiles used air-flow and gravity. These natural principles allowed the sculptures to speak for themselves.

In essence, the philosophy of kinetic art was simplicity. The sculptures use minimalistic design elements to allow the motion and inherent scientific principles of the sculpture to speak for itself. Many of the creations displayed particular aerodynamic and physics-related concepts. These artworks mimicked and mirrored the way in which nature revealed itself in our daily lives. These sculptures were an attempt to consolidate art, science, and nature; to create visual harmony between them. Every aspect of the sculptures was meticulously engineered, despite their apparent simplicity.

KINETIC ART TODAY

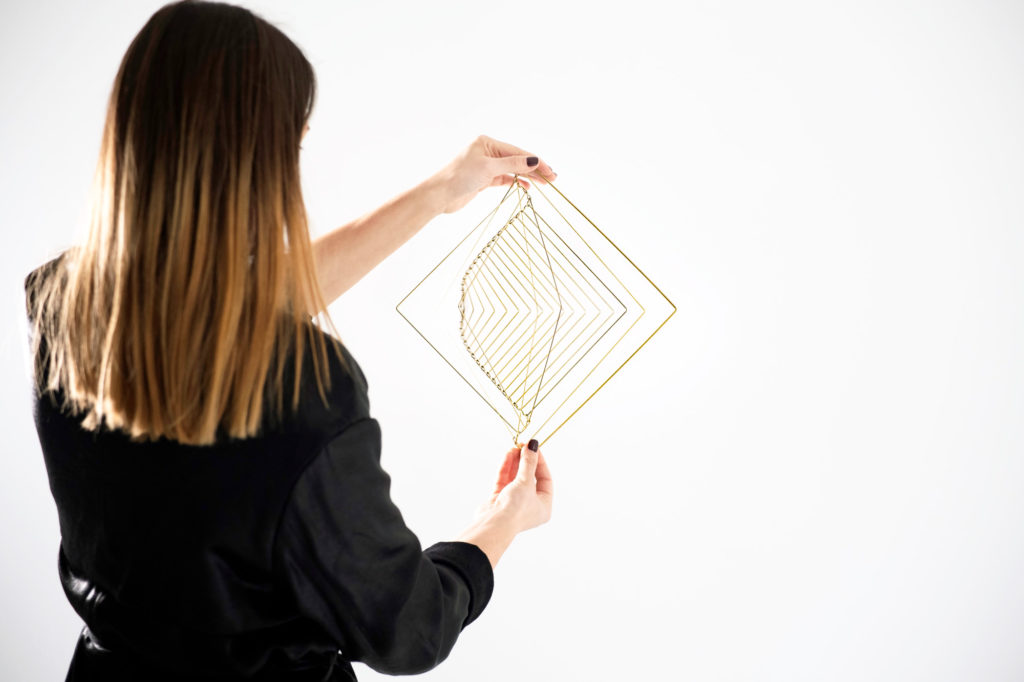

Kinetic art appeared on social media after videos of the Welsh artist, Ivan Black. His Nebula Ellipse, Cubes and Square Wave sculptures went viral on Instagram. Black, is in many ways, the modern evolution of artists like Calder and Gabo. He attempts to explore many different disciplines of mathematics and science. His hypnotic sculpture, Square Wave is often used to teach about the Fibonacci spiral that is frequently found in nature.

All of Black’s works have an essential meaning attached to them aside from their mesmerizing beauty. They aim to inspire us and to reflect on our surroundings and to relate his art to the phenomena of the natural world. In fact, it’s no surprise that the sculptor’s inspirational pieces ended up in the Peggy Guggenheim and Kinetica Museums. Black has managed to jolt himself forward as a primary champion for the kinetic art movement. Via commercialization and social media, he put kinetic artworks on the map for the general public.

New Ways to Engage with Artworks

In a modern age of information overload and intense stress, peaceful and calming statues such as Square Wave can help us to reflect and process what surrounds us. Studies have shown that kinetic artworks are a great way for individuals to engage with science and nature. This visual and physical medium offers passive opportunities for individuals to educate themselves. The history of the mobile art movement helps to inform its future, as it develops we have a duty to build new understandings of what that means for us; a duty to interact with art rather than motionlessly consuming it. As the opportunity to be passive surrounds us, kinetic sculptures send an important message: no matter what discipline or profession we have, we should feel a responsibility to try and make our world as engaging and educational as possible, we should try to elevate ourselves.